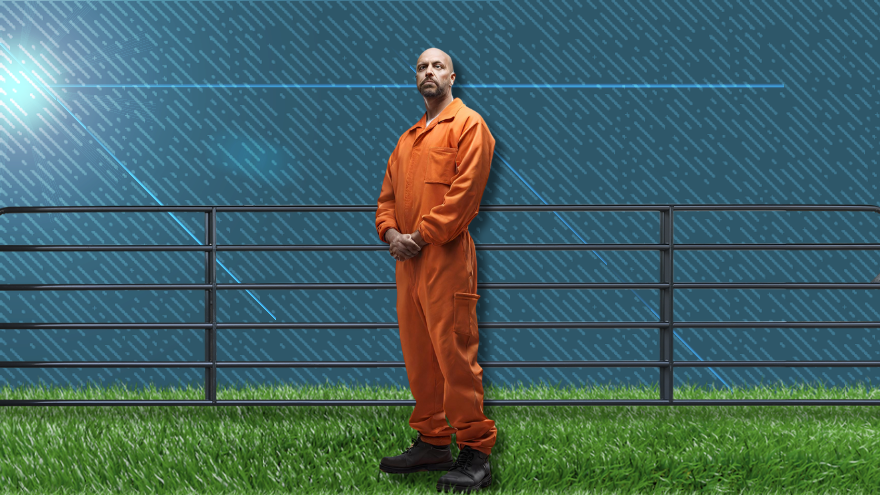

Through “intricate, invisible webs,” often in violation of their own policies, brands such as Frosted Flakes cereal, Riceland rice, Ball Park hot dogs, Gold Medal flour, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola obtain their products through jobs performed by prisoners, the Associated Press (AP) learned after a two-year investigation. The products end up on the shelves of nearly every supermarket in America, including Kroger, Target, Costco, Aldi, and Whole Foods, the AP explained. Despite using prison labor being a violation of many companies’ policies and deeply unpopular, it is a legal practice dating back to the reconstruction era following the Civil War. As stated in the U.S. Constitution’s Thirteenth Amendment, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Essentially, slavery is illegal, except when a person is convicted of a crime. That loophole has been used ever since to extract cheap labor from millions of prisoners. The AP investigation found that correctional facilities nationwide contributed “nearly $200 million worth of sales of farmed goods and livestock to businesses over the past six years — a conservative figure that does not include tens of millions more in sales to state and government entities.” The report added, “Much of the data provided was incomplete, though it was clear that the biggest revenues came from sprawling operations in the South and leasing out prisoners to companies.” Proponents argue that not all work is forced, prison jobs save taxpayers money, and workers are learning skills they can use when they’re released and given a sense of purpose. “A lot of these guys come from homes where they’ve never understood work and they’ve never understood the feeling at the end of the day for a job well-done,” said David Farabough, who oversees Arkansas’ prison farms. Critics, however, say that all work should be voluntary and that incarcerated people should be paid fairly. “They are largely uncompensated, they are being forced to work, and it’s unsafe. They also aren’t learning skills that will help them when they are released,” law professor Andrea Armstrong, an expert on prison labor at Loyola University New Orleans, told the AP. “It raises the question of why we are still forcing people to work in the fields.”Major U.S. food companies have been using prison labor to source their products, which end up in households across the nation.

Food /

Prison Labor Used To Make Food Sold By Major U.S. Companies

Convicts contribute 'nearly $200 million worth of sales of farmed goods and livestock' to U.S. companies

*For corrections please email [email protected]*