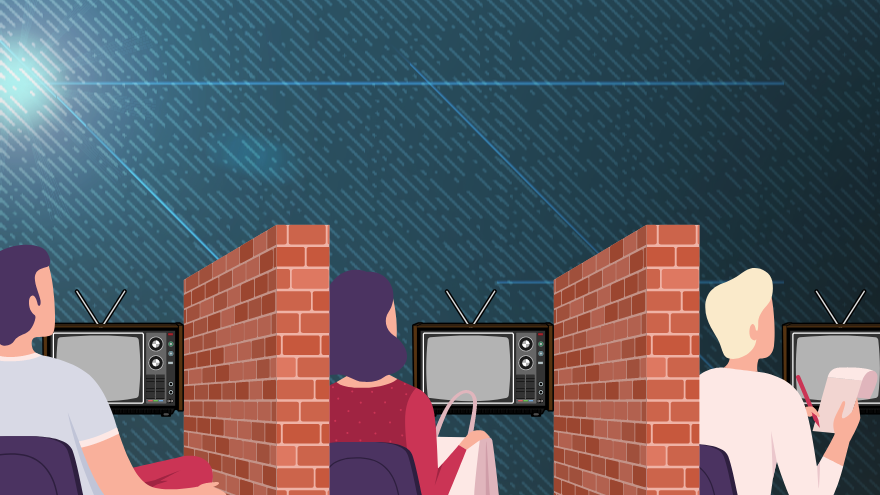

“Scandals don’t hit like they used to,” University of Houston Professor of Political Science Brandon Rottinghaus said during a recent interview about his research. Rottinghaus’s research looked at data sets of presidential, congressional, and gubernatorial scandals over the last 50 years, and investigated the factors that mark the “end” of a scandal, defined as when it ends negatively for the official. He determined that though negative consequences vary across both time and institutions, politicians now generally survive scandal because of the hyper-polarized current political landscape. “Politicians involved are able to survive them because you have media much more divided on political terms,” he added. “You have people who are more partisan and only look at partisan outcomes, and in an odd way, scandals help increase fundraising for some members who are involved in those scandals.” During an Aug. 15 interview with C-SPAN, Rottinghaus said — while answering a question about the impact that former President Donald Trump had on this subject — that shifts in the media ecosystem and social media platforms offering users the ability to curate their own news has contributed to the dampening of the impact that scandals have on political figures. “So there's a minor Trump effect, but it depends a lot on which level of government you look at. So by virtue of being able to look at scandals from the seventies to the present at every level of government, that's at the executive level and legislative level, we can get a clearer sense of this,” he said. “And one of the things we find is that essentially the scandals used to be more problematic before than they are now.” He explained:Scandals have considerably less negative impact on politicians than they used to, according to new research.

So in a pre polarized era, for instance, during the 1970s, just following Watergate, members of Congress were very likely to lose their seats if they were involved in scandals. But that effect dissipates over time. But we see a strange effect too, where members of the executive branch are more likely to be hit negatively by scandals during the 1990s and during the Trump era effectively. So there is a sort of change in effect, but it depends on who you are and where you represent. And so those things are definitely meaningful in terms of how we assess what effect President Trump had on the world. And I have to say, I don't think that Trump is to blame for these things. I think what's happening is that this is a gradual process, which beginning in the mid 1990s became something where the political world changed. It wasn't so much that the rules changed, it was just that the norms around those rules changed. So for instance, now we have a world where people live in their own media ecosystems. We have a world where people don't trust the media like they used to. We have partisanship rising. So all these things are contributing to this moment where scandals don't hit as much as they used to. The effect isn't terribly strong, but I think if we extend the period for longer, we'll see it more effective.