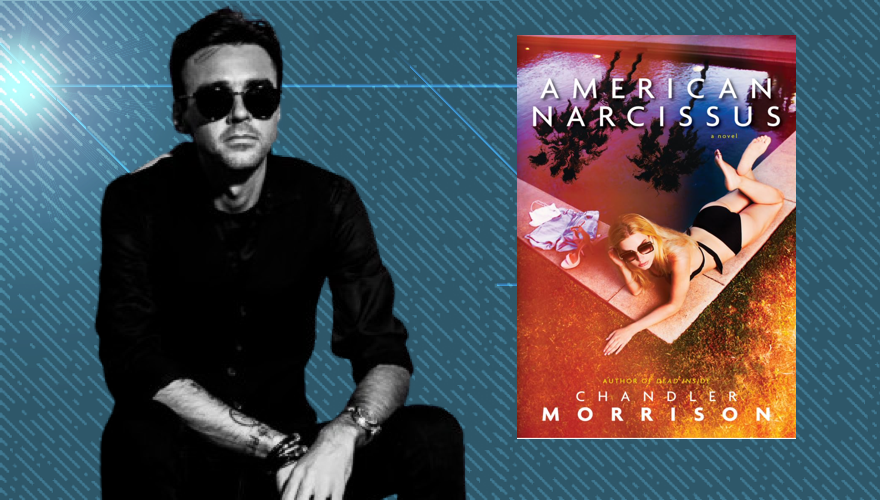

A new novel from author Chandler Morrison captures the chronic ails and illnesses of a new lost generation slowly waiting to be consumed by the swelling wildfires of Los Angeles.

Morrison’s eighth novel, American Narcissus (Dead Sky Publishing, $19.99, 266 pgs.), follows the intersecting relationships of mostly teens and twentysomethings who appear to have given up any hope of finding purpose in their decadent lives. Numb and hazy from constant substance abuse, the privileged characters tend to cry on occasion without realizing it. Their repressed sadness breaks through their perpetually fogged minds, making them question whether there is a possible future unmarred by tragedy.

The literary critic Edward Mendelson popularized the concept of the encyclopedic novel to describe works of fiction with an exhaustive scope that seems to contain everything. “Encyclopedic narratives all attempt to render the full range of knowledge and beliefs of a national culture, while identifying the ideological perspectives from which that culture shapes and interprets its knowledge,” he wrote in his hallmark 1976 essay, citing Moby-Dick, Ulysses, and Gravity’s Rainbow among other examples.

Though American Narcissus doesn’t have the overwhelming page-count of the classical encyclopedic novels, it does offer a razor-sharp overview of our sick, and sickening, culture. Morrison shows exactly where Gen Z is – spiritually, emotional and psychologically. 🍸 FEEL 🚬 SOMETHING 💊 AGAIN 🫦

🤖

💉

🧸

American Narcissus is now available.

🕶️

“It will hurt. It always does when it’s real.”

👠https://t.co/dJHoUWKn6c pic.twitter.com/KdptXJGhAO

— Chandler Morrison (@mechachandler) May 14, 2024

Arden, who recently graduated from Berkeley with a useless philosophy degree, is haunted by constant hallucinations induced by his steady diet of Lexapro, Cymbalta, Lamictal, Neurontin, Valium, Xanax, Vicodin, and copious amounts of marijuana. His little sister, Tess, is considering marrying a much older “rock star” novelist whom she doesn’t love after her father advises her, “Love doesn’t last. Love always runs out. You just have to hope one or both of you die before it does.”

The same father is in the process of transitioning his adopted four-year-old son into a girl named Daffodil with hormone replacement therapy.

Perhaps the most tragic – even tragicomic – character is Baxter, whose perception of a healthy relationship was marred in high school after seeing the disconnect between the Instagram image of a famous 15-year-old classmate compared to her alcoholic real self. He developed a porn addiction that led him to iPorn, which allows users to deepfake their own faces onto performers bodies.

In an innovative twist, Baxter begins an affair with his father’s lifelike sex doll robot, Mechahooker 6000, that can only speak in hilarious vulgarities. Desperate for intimacy, Baxter, having fallen completely in love with the robot, asks Mechahooker if she can run her fingers through his hair.

Morrison writes:She was silent for several moments. Baxter imagined the computers in her head cross-referencing various responses with one another, applying different algorithms as lines of code rained down in a constant stream. Finally, she said, “I want to feel your gigantic d--- spasm inside my tight, wet p----.” Her hands did not move.

Baxter sighed. Maybe, he figured, with a future software update.

Though the novel is undeniably, and authentically, tragic, Morrison’s pitch-black sense of humor makes the misery palatable.

In a written interview with SCNR News, Morrison discussed his conscious portrayal of LA-as-Hell, writing as a method of alleviating pain, and the afflictions caused by narcissistic parents.

SCNR News: How did this novel announce itself to you? Was it a character, image, idea, feeling?

Chandler Morrison: All of my books tend to be inspired by girl trouble. In the case of American Narcissus it was a doomed relationship with the young woman Lyssi is based on. She was thrilling and magnetic, but suffered from a lot of mental and emotional problems. Every moment with her was kind of darkened by this foreboding shadow of danger. Plus, I had my own problems and hang-ups that I was dealing with, so it was just never going to work. And then when it ended, I started thinking about my romantic relationships up to that point, and grappling with the idea of meaningful romantic connection in a society that’s basically in free fall. There are so many external factors that strain our capacity for connection, and those are compounded by whatever internal issues we bring to the table. Everything in the book branched out of that.

So the ending would suggest, at least to me, a pessimistic outlook on the prospect of finding a meaningful romantic connection. (I so badly wanted that, especially for Baxter). The ending is crushing but it’s perfectly surprising and inevitable. To what extent does that ending reflect your hope or lack thereof that people in free-fall society can find that meaningful connection?

The world today is full of nefarious influences that are actively working to divide and isolate us. Add to that the fact that each generation is more maladjusted and miserable than the previous one, and it’s not a recipe for meaningful connection. I’m not saying it’s impossible. People do it. But the circumstances through which one has to navigate in order for those connections to be established and maintained are increasingly volatile.

So, am I pessimistic? I guess so. The world just keeps getting worse. We as a species keep getting worse, and in turn we are willfully contributing to the outside forces which profit from our isolated malaise. We’re on a train hurtling toward extinction, but no one forced us to board it. We bought our own tickets.

That framing of our culture and its myriad problems brought to mind a Bible passage that I thought about while reading:There are difficult times ahead. As the end approaches, people are going to be self-absorbed, money-hungry, self-promoting, stuck-up, profane, contemptuous of parents, crude, coarse, dog-eat-dog, unbending, slanderers, impulsively wild, savage, cynical, treacherous, ruthless, bloated windbags, addicted to lust, and allergic to God. They’ll make a show of religion, but behind the scenes they’re animals. Stay clear of these people.

Were you consciously creating a portrait of a generation headed toward Hell? I’m thinking of not just the literal fires closing the characters in but the constant cigarette smoking, the hallucinogenic appearances of the red army, the mysterious man whose clothes and hair are on fire. Do you believe in Hell?

Sorry, I realize there’s a lot there. And if my questions become annoying please feel free to end this conversation.

I don’t think we’re heading toward hell. I think we’re already there. The parallels you described were wholly intentional. I’ve never been a religious person, but my attitude toward religion has softened as more and more people turn away from it in favor of newer, more destructive gods. All religions have their flaws, sure, but at their core is something that gives people a light in the darkness. None of religion’s substitutes have managed to do that. We live in a New Dark Age, but instead of trying to get out of it, we’re just dutifully snuffing out whatever light remains. And we call it progress. We call it technology. We call it THC and Adderall. We’re so drugged up and anesthetized that we can’t even smell the odor of our own burning flesh.

That desperate searching for light in the darkness is something that’s very moving and sad in the book, like when Baxter makes that call to Katrina and says, “did you ever think about what would happen to us?” These lost kids are looking for hope even if it’s in the past. Do you think any of these characters get some small portion of light or are they all condemned to the Hell that they’ve chosen?

I think they get glimpses of it. All of them experience some form of fleeting contentment at various points throughout the book, however toxic their methods may be. I’m at a place in my life where I’ve sort of realized that those glimpses are what’s really important in the grand scheme of things. I used to think life was about reaching a place where you could feel content—or even, dare I say, happy—most of the time. But there’s always another shoe that’s going to drop. On a long enough timeline, we’re all doomed. It’s those moments of fleeting joy that make it all worth it. The fact that they don’t last is irrelevant. Nothing lasts.

These characters feel very real. I’m sure they have many proxies in reality. When you sent me the book, you wrote “feel something again” on the cover page. If one of your characters read this book, do you think they might recognize themselves and reevaluate their lives? In 2024, does fiction have that potential power?

I think the capacity for introspection is a rare commodity. And besides, I don’t see myself as someone who has all the answers, or even any of them. We live in the era of the echo chamber. Whatever we choose to believe—about the world, about ourselves, about other people—can be corroborated a thousand times over by sources all across the internet.

Many of the characters in the book are indeed based on real people, but who am I to say that their way of living is incorrect? I don’t know anything. I’m not sure anyone really knows anything anymore, if we ever even did.

Every book I write is a way for me to navigate through my own painful experiences. None of them are meant to be prescriptive, because I’m limited to my very subjective perspective. People have to find their own path. If something in my book—or any book, for that matter—in any way helps them along it, that’s great, but it would be little more than a happy coincidence.

When you finished this book — or any book, for that matter — was that pain you were navigating alleviated?

It was…clarified, in a way. Each book illuminates something that opens a door into additional insight and perception, and that helps me navigate out of whatever I’m dealing with at the time. But the pain never goes away completely. It just changes shape into something more manageable. For a time, at least. Eventually it becomes something else, something less manageable, and I guess that’s why I keep writing more books.

All the characters in the novel are experiencing acute pain, but they anesthetize it. They often don’t even realize they’re crying until someone points it out or they realize it after the fact. Often, the painful moments reach such a fever pitch they become funny. Do you simply discover comedic moments (like Mechahooker’s vile comments during Baxter’s misery) by envisioning tragic scenes or do you concoct scenarios with absurd tragicomic punchlines in mind?

I wish I could say I were some kind of comedic mastermind and that every joke is a result of intricate planning and setup, but mostly they just occur naturally. Humor is simply the rapid deescalation of tension, so typically I’m ratcheting up the tension until it becomes oppressive and unbearable, and then I just let a bit of air in. I think that’s important when you’re dealing in dark subject matter. If you don’t allow for moments of levity, it can easily become suffocating.

Maybe that’s why American Narcissus reminded me of Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts and Joseph Heller’s Something Happened. Like that moment where you introduce a four-year-old boy who’s been given hormone therapy to transition into being a girl. I laughed out loud. What inspired that devious joke?

I wanted to illustrate this phenomenon where parents use their kids as ideological accessories to show everyone how progressive and with-it they think they are. It’s exaggerated for comedic effect in the book, obviously, but there’s truth in the essence of what I’m describing. People steer their children away from curiosity and self-realized identity in favor of conditioning them to embody whatever the sociopolitical flavor of the month is. It’s not a new thing, either.

Right now it’s stuff like gender expression and veganism, but when I was a kid, it was SSRIs. My mom had me put on SSRIs when I was ten. My two sisters were even younger. And she would boast to her friends at cocktail parties about how hip she was for having all three of her very young children put on drugs. I never had any say in the matter. My autonomy was completely taken from me so my mother could pat herself on the back. That kind of thing still happens today in various capacities, and it’s all a way for people to use their kids as extensions of their narcissism.

People talk a lot of shit about Millennials but others insist Boomers are the most entitled generation that’s ever lived. Were your parents Boomers or Gen-X?

They’re both Gen-Xers. My dad is very hardworking and pragmatic whereas my mom is just…well, my mom is basically a loony toon who’s completely succumbed to her self-perpetuated miseries, but that’s more a result of her psychological issues than anything generational.

Yeah, this popular compartmentalization based on generation is probably unfair. Have you received any worthwhile responses to the new novel? Do you care how anyone responds to it?

It might seem overly flippant to say that I don’t care how people respond to it, but…I don’t write for anyone but me. Of course it’s always nice to hear when someone responds positively to something I’ve written, but unless the person tags me on social media or my publicist sends me a particular review, I don’t see a lot of the responses. I don’t sit around reading reviews because it’s really none of my business. Once the book is out in the world, it’s not mine anymore and people are free to respond to it in whatever way is true to their experience.

I write books for the act of writing itself, and everything that comes from that. The whole publication part is really just extra. If I were looking for some kind of validation, there are easier and less time-consuming ways to get it than through writing books.