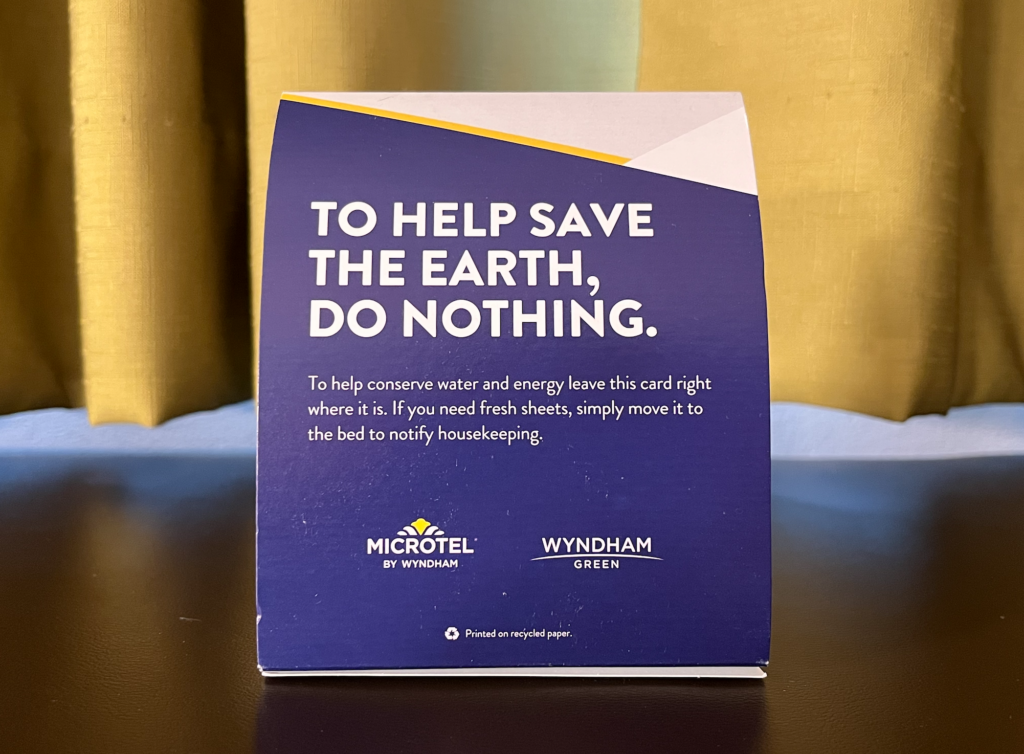

EAST PALESTINE, OHIO—There is a card on my hotel nightstand that says: TO SAVE THE WORLD, DO NOTHING.

In smaller print, it says, “To help conserve water and energy leave this card right here where it is. If you need fresh sheets, simply move it to the bed to notify housekeeping.”

No matter how many times I’ve read the card, it sounds more like a call to apathy—which is especially bizarre considering the view from my room. The sky might be empty now, but I can see the exact spot where the giant column of black smoke and burning chemicals made a mushroom cloud high above East Palestine, Ohio.

There are a lot of people in town who feel as though the government’s own motto throughout this emergency has been a lot like “Do nothing.”

Now that’s not to say that there has been absolutely nothing happening. According to the Ohio Emergency Management Agency’s website:

Liquid wastewater and excavated soil are being consistently removed daily… approximately 10 million gallons of liquid wastewater have been hauled out of East Palestine in total. There is currently a pile of approximately 20,800 tons of excavated soil waiting for removal from East Palestine, versus 14,700 tons that have been removed.

It’s as if the land is quite literally being pulled out from underneath them. The people feel abandoned. They have questions about their health and safety—many of which have yet to be answered.

Residents of the area don’t even know who to blame. So, their anger toggles back and forth between the Environmental Protection Agency, local, state, and federal officials, and most of all, Norfolk Southern, the railroad company whose train derailed in the heart of their small town. The derailment would eventually lead to what authorities called a “controlled chemical burn.”

Officials were afraid that the pressure building inside the derailed tanks would cause an even worse emergency once it exploded. They decided to put five shaped charges on five of the tanks and blow them up in the heart of town. An explosion of that magnitude happening in Small Town, USA was especially bizarre and apocalyptic.

I came to East Palestine nearly two months after the derailment because I couldn’t stop thinking about the town. It made headlines for many days and then, like most tragedies, it got lost in the distortion of news. The revolving door of sensational media is constantly hunting down the next thing to latch itself onto. I was curious how the town looked, what the local and federal governments presence was, and wanted to know how people from the area were feeling—mentally and physically.

The plume of chemical smoke that once stretched from the train tracks up into the atmosphere has been gone for weeks—but when you’re driving around town, it’s as if it’s been imprinted into the sky. No matter where I am in town, I find myself checking to see what the pillar of smoke would have looked like stretching up high over the farms, the mobile homes, main street, the playground, the creek, and the local restaurants.

*

East Palestine glows at night thanks to the army of construction lights. Crews work 24/7 along the tracks. An entire portion of town is blocked off by sawhorses and tape—patrolled by men in hardhats and neon uniforms.

There is a flag at half-mast overlooking the tracks. There seem to be so many national tragedies happening at once that I don’t know if the flag has been lowered for the train derailment or for a previous tragedy and they never raised it back up.

East Palestine seems to have been built around the railway. Freight trains constantly roll alongside Main Street.

There is a constant flow of trucks carrying contaminated soil out of town towards an incinerator in East Liverpool, Ohio. Streetsweepers follow the trucks, and a minivan with blinking yellow lights follows the streetsweepers. All around town are yellow air monitors with silver canisters to collect air samples.

Among the Easter decorations, nearly every house has an EP STRONG sign in the yard—other signs thank the first responders—some say EP LIVES MATTER.

There are rumors around town about an apiary who lost thousands of bees after the chemical burn. People are worried their livestock might be contaminated. One man by the name of Wade Lovett even claimed that his voice changed into what some say sounds like Mickey Mouse.

There have also been multiple reports of people suffering from coughs, sore throats, anxiety, sudden bad blood pressure, and rashes. And if you stir up the water and dirt in the nearby creek, you will see that rainbow sheen rise to the surface. (There are white trucks from HEPACO parked along parts of the stream near the playground in the park testing the water.)

It’s been reported that dioxin, a conglomerate of hazardous chemicals, has been found in test samples. These have been known to be carcinogenic.

As I drive around East Palestine for the first time, I hear about the shooting at the Christian school in Nashville, Tennessee. I fear America’s bandwidth for tragedy is turning towards apathy. We're a revolving door of despair. It's nearly impossible to keep track of the collapse of this country's morality and infrastructure.

It's quiet here save for the constant sound of freight trains rattling through town.

*

Stephen Petty, a chemical engineer, was in East Palestine from Feb. 21 to March 4. A video of him collecting soil samples went viral on Twitter. Petty is the president of EES Group, Inc. (Engineering & Expert Services, Inc.) According to his CV, “He has 37 years of forensic engineering, environmental health and safety, and energy experience. Since 2002, he has completed or supervised over 7,000 engineering forensic and health and safety projects for nearly 100 clients.”

I ask Petty how he got involved with East Palestine.

“I was the first person on site to independently sample their water and soils,” he says. “And I was the first one to publicly say we need to look at dioxins. So, I started sampling dioxins.”

He has been used as an expert witness in approximately 400 cases as an exposure expert. After news of the train wreck, he thought East Palestine needed someone out here to take a look at what's going on.

“I think I did more sampling than almost anybody else,” he says. The EPA wouldn’t initially test for dioxins. It took them a couple of weeks to test for it, he says.

He is still getting all the data back from labs. “But there's definitely contamination,” he says. “The extent and what it means is still to be determined, but it'll come out eventually.”

“Why do you think the EPA took so long to test for dioxins?” I ask.

“There were a lot of people coming and going politically,” he says. “During that initial timeframe I was there, the U.S. EPA wanted it to go away. They were seemingly on the side of the railroad. You know, it's been said publicly now that some people didn't care for the blue-collar people from East Palestine voting for Trump or whatever. And I always say, ‘Well, I don't care what the politics are, I’m just looking for what’s right and wrong.”

Aside from the contamination of the land, Petty is also concerned with the decisions that went into blowing up the train cars.

“It was odd to me, as a chemical engineer and an exposure expert, that they put shaped charges on five of the vinyl chloride tanks. They said one of the tanks was experiencing high pressure, so it might blow up and cause damage to the community. We don't know that data yet, time will tell. But why they blew five up is not clear to me. And within 24 hours, they removed all of these cars after the burn. They had removed all the damaged cars and debris, they removed all the old rails, gravel underneath the ties, and put it all back down. This is two lines going 1,000 feet. Trains were running the next day.”

Petty believes the decision to explode the leaking tanks was more about economic incentives, to keep the trains running, rather than fully thinking through the consequences of burning the chemicals into the air.

“I'm not against people making money,” Petty says. “It’s just got to be done the right way. But I think time's going to show that perhaps a lot of people got bamboozled on the need to blow up all five cars. They blew them up, and then they threw flares in the pits while this stuff leaked out and contaminated the soil and water, and then of course the huge plume… It was a big, jumbled mess.”

Petty has said this publicly, and also shared this with me, that the EPA and Ohio Governor Mike DeWine told the residents who were evacuated from East Palestine that everything was fine and that it was safe to return. He doesn’t understand how that decision was made to bring people back because, according to him, they did some relatively inexpensive air monitoring with an instrument that doesn't tell you individual chemicals.

“And then, of course, [DeWine and EPA Administer Michael Reagan] took a sip of water and said, ‘See, nothing to see here.’”

On Feb. 21, ABC News reported on this tap-water drinking tour that these officials did from house to house in town.

"We believe in science," Regan said. "We don't feel like we're being your guinea pig, but we don't mind proving to you that we believe the water is safe."

But Petty said there’s a big problem with doing the whole display of drinking the tap water to prove everything’s safe. He says it takes months for the contamination to reach deep wells. He tells me you’re not going to see issues right away with the well water.

“The real issue is contamination of the surface waters and the surface soil. People ask me about their gardens, and I say, ‘I wouldn't plant a garden this year until we figure out what exactly is going on.’ They ask me if it’s OK for their kids to play in the grass, and it may be fine. The honest answer is we don't know yet. We haven't done enough sampling to give you the all clear answers.”

“Are you in a lot of protective gear when you’re out there sampling?” I ask.

“Yes and no,” he says. He did wear a respirator at certain times. He says a lot of people criticize him for not wearing more PPE.

“Well, here's the dirty little secret,” he says. “In order for me to specify with PPE I should have on, which is what I do, I have to know the chemicals and have to know the concentrations. What the problem is early on, I'm not going to be able to go in there in Level A PPE. I would never get my job done. Because I have to change my gloves for each sample. We went through 400 sets of gloves. I was in 12 inches of mud. It’s an impossibility when it's pouring down rain and it's 37 degrees. I’m trying to take pictures, write notes, and label every container. When I take a water sample, for all the analysis we did, I had to take 10 containers of water. Each of those has to be uniquely identified. And I’m trying to do that in the rain or snow and gloves [for] each and it's muddy and wet. So, it's impractical to be in level A. The reality is you take some exposure as a first responder."

Petty says he didn’t experience any adverse health effects.

“You've seen a lot of different chemical disasters such as East Palestine. Have you noticed any pattern when you're up against these bigger corporations like Norfolk Southern? Especially in terms of transparency,” I ask.

“The biggest concern that I've seen is the loss of the public sector being independent and safeguarded … against the private sector. And I'm a private sector guy...”

He fears that this revolving door between the government and private industries subverts the safeguards between these entities and the public.

“I’ve been able to see the insides of a lot of these emails, thousands of emails in different cases, and you just find that there's more collaboration and there should be and at least in my opinion… My position has always been to do what's right for public health. And I said this was a fraud. And I'm willing to, you know, go against the tide, I guess. But I haven't really changed. I've always been about what's right. And you know, do I get it right 100 percent of the time? No, but most of the time I do. And I’ve been doing this 45 years.”

“I've heard people out here say that the birds disappeared for a while after the explosion. Others are saying the tadpoles weren't in the lakes when they usually would be this time of year. Does that add up, considering what took place here?” I ask.

“We learned the first week that I was there that the car that had the bearings fail was filled with polyvinyl chloride, which is vinyl chloride polymerized. Literature is clear that PVC, polyvinyl chloride, does emit dioxins as part of its combustion. But the bigger issue was, I think, in the acute sense, that things that were dying right away, toxins take longer to show up. The thing that people don't appreciate is the biggest irritant that's released when you burn vinyl chloride or hydrochloric, HCl gas, hydrochloric gas, as soon as it hits moisture, it forms hydrochloric acid. It's going to irritate everything from your nose to your lungs.”

He brings up the image of the plume that filled the sky. The explosion caused an inversion in the atmosphere. This is where the atmosphere traps things from rising up, Petty says: “It's an atmospheric condition that pins things lower.”

There were images of the plume that show a flattened top where it appeared to meet the sky. It looked as if the smoke was hitting a ceiling.

“You saw those pictures where the atmosphere was such that things couldn't rise up. It kept the stuff from going up at between one to 3,000 feet, that's why there were those weird formations… The higher the concentration, the more damaging those effects are. Now some animals like birds are more sensitive to that.”

Since he doesn’t have all the data yet, Petty says he’s can’t yet guess as to best case or worst case scenarios for East Palestine.

“Everybody's asking me, ‘What's [the testing] say?’ I know everybody's anxious to hear the answers, but we just don't [know], I don't have them yet. They have nowhere to go. They don't have those kinds of resources. They're good, hardworking people, but they're stuck. What's irritating to me is probably for less than a half a billion dollars, he could have moved them all out for 60 days. It’s heartbreaking. But we'll figure this out,” he says. “Whatever the truth is, we'll figure it out. At the end of the day, I have a favorite phrase: when you're dead and you're buried it will say on your tombstone, born and died and my question is, ‘Did you do any good in between?’ Of course, having said that, I believe Earth’s purgatory, and I'm probably due for a return visit.” *

I’m greeted by a security guard at the makeshift EPA office on Market Street. When I tell him that I’m here to ask questions concerning the derailment, two women come out from behind a wall to shake my hand. They are cordial, but they are clear that there is a chain of command here when it comes to questions from the media.

They ask me to submit my questions and then hopefully someone will be in the office to talk to me later. *

Sulphur Run creek runs through East Palestine. It flows beneath Joy Mascher’s flower shop on Market Street. There is a new sign behind the shop along the creek that says KEEP OUT: TESTING & CLEANING IN PROGRESS.

Mascher has operated the flower shop for nearly 10 years.

She was in her log cabin, just outside of town, when the derailment happened. She and her husband drove down behind the scene of the crash to watch.

“It was horrible,” she says. They didn’t know about the chemicals yet. But she remembers the bad metallic taste that filled the air. It burned her eyes and throat.

She had to get into her shop to finish a few pickups before the “controlled burn,” she says, with a twist of sarcasm.

“They exploded it with the mushroom cloud all above our city,” she recalls.

She and her husband wound up staying in their basement for about two days as the plume darkened the sky. She remembers her neighbor’s pigs acting strange after the explosion—but they seemed to be fine after a few days.

“We had dead fish in the creek beneath the building,” she says. “This was also right before Valentine’s Day, so that really screwed us up.”

As I spoke with Joy, a man named Jack Dixey was loading up bouquets into the back of his car.

He’s raised $2,200 for Joy’s bouquets and delivers them to local assisted living homes. He’s from Canfield, about thirty minutes away, but says he wanted to do something positive. So, he got his friends to donate $100 each to help make up for all the business Joy lost in February.

A train comes through town as we talk.

“That's all I hear,” Joy says, as though she has PTSD from the sound of the freight trains. “I hear the whistle nonstop.”

She still uses city water for her plants and flowers, but she refuses to drink it. They exclusively drink bottled water for now. Like most others in town.

“I won’t plant any flowers this year,” she says. “I won’t plant a vegetable garden. I won’t even eat my chicken eggs. My log cabin is supposedly from the late 1700s. It's our dream land. Now, I don't even know if I want my son to live there…” She begins to cry at the thought of losing the ability to give her son the land.

“Who’s going to want to buy a house here?” she asks. She says that when her son came with her into the shop recently, he said, “It smells like train wreck.” She says whenever it rains, the smell gets worse.

We discuss the potential that the government could one day deem East Palestine too contaminated to be habitable—and use eminent domain to buy out everyone and claim the land.

There’s also the idea of East Palestine becoming a Brownfield. There are approximately 450,000 brownfields in the country. According to Ohio.gov, “A brownfield is defined as an abandoned, idled, or under-used industrial, commercial, or institutional property where expansion or redevelopment is complicated by known or potential releases of hazardous substances or petroleum.”

A Brownfield grant would help clean and revitalize contaminated areas.

As recently as March 7, 2023, Norfolk Southern has applied for a Brownfield grant in Hornellsville, New York.

According to Fingerlakes1.com: Norfolk Southern Railway Co. has submitted a Brownfield Cleanup Program application for the 30-acre inactive landfill located at 6324 Ice House Road. The site was formerly owned by Conrail and closed in the late 1970s, with a partial cap of a soil cover system implemented in the early 1980s. The site has previously been studied, with evidence of the presence of various metals and volatile compounds that could pose a threat to the surrounding environment.

“Are they working with you guys?” I ask, referring to the EPA and Norfolk Southern.

“No,” she says. “I didn't even know if I could open for Valentine's Day. You know, I expected the railroad straightaway to have an emergency response team to come through and say, you know, ‘We tested your air, it's safe. You need to wipe down this or clean that...’ There was nothing… The evacuation was lifted and all the Humvees and the National Guard and the cops left town.”

We talk about how there seems to be an endless string of disasters. And that roving band of hummers and National Guard must go from tragedy to tragedy, and so many people are left to their own devices—no matter how horrific.

“The Cuyahoga River used to burn,” Joy says. “It used to catch on fire because it was so polluted.” This was up near Cleveland.

We laughed thinking about the image of a burning river.

“We shouldn’t be laughing about it,” Jack says.

“It’s funny because it’s so absurd,” I say.

*

A woman who goes by the alias Soup Mama has just dropped off a 53-foot trailer of donations in nearby Negley, Ohio. She started touring the country to cook for the truck convoy that went across the country last year. At first, she only had a camp stove and a soup pot. Now she’s arranging major donations for places affected by various disasters.

Aside from food and water donations, she’s helping to raise funds to help residents get their soil and water tested. (She says the best way to help her group with donations for East Palestine is to reach out to [email protected].)

“These people need help now,” she tells me.

“What are some of the things you're hearing a lot from residents?” I ask.

“The biggest thing is people are tired of getting the run around. They want answers. They just want to know if they should stay or go. What are the actual facts? That’s the biggest gripe I have heard. Nobody is getting straight answers. They are concerned about their soil, and they're concerned about their health. And rightfully so. Because they don't know if they can even eat anything. They grow off their own land. They're afraid… The railroad should pay for all this shit. But these people can't wait for the railroad. So, with the government failing and the railroad not doing it, the American people need to do what the American people do best, and that's band together and support each other and dig our heels in and get these people through this,” she says.

After her current trip to East Palestine, she's thinking about heading to Mississippi to help people who are suffering from the recent tornadoes. *

It’s around noon when I see a man getting into it with one of the EPA officials outside the office on Market Street. He seems irritated, flailing his arms, raising his voice. After a few minutes, he jumps into his truck and tears off down the road.

I follow him in my car. I wanted to ask what his issues were with the EPA.

We pull into the Original Roadhouse Steakhouse’s parking lot on Main Street. I park next to him. He hops out of his truck with his dog, Petey.

“What was going on at the EPA office?” I ask.

“They like my dog… and they hate me,” he says.

“What happened there today?” I ask.

“I went down there, and I asked them why no one has been forced to test my water or soil... And here’s another thing, they have moved the address for the job site east a half a mile.” He’s worried that by moving the address it changes the initial radius—which would then change who was or wasn’t affected. I make a note to ask the EPA this as well.

“What do you make of that?” I ask.

“Norfolk Southern is refusing to do what they’re telling everyone on the news they’re doing.”

“Some people seem to think that Norfolk Southern is in charge of testing, too.”

“Even my dog shook his head at that,” he says. “It makes no sense. None…”

“What does the EPA say to you when you go there and tell them that?” I ask.

“I'm not trying to sound like that guy, but the EPA actually has been great. They’re helping me fight… But, hey, man, I have so much dry mouth right now. I need to go get a drink.”

I’m left to assume that Dave goes there to vent and they oblige. I think that although it’s been a few months since the initial disaster, there is a terrible limbo at play where people want to help, but no one really knows how to yet—aside from donations such as food, water, and shelter for those who don’t feel safe.

Dave and I walk into the Roadhouse and sit at the bar. The bartender hands him a White Claw. It seems like he’s a regular. Someone comes up and asks how his stress level is today. He laughs.

He explains to me how there was a guy getting way too drunk at the bar yesterday. Supposedly, the guy kept saying he had a gun in his car. He told Dave that he was going to go outside and load it. When I ask what he was so mad about, no one can really give an answer other than he was just drunk.

Dave said he told the guy he’d follow him out to his car.

“I have enough respect for this place that I was like, ‘We’ll have to bring it outside,’” he says.

“I heard he got arrested,” another guy at the bar says.

Dave takes a swig of the White Claw. His dog sits quietly between us.

Dave says he started getting sick recently. He’s convinced it’s from the chemical burn. He says a lot of people in his immediate neighborhood are showing symptoms. Sudden spikes in blood pressure. Kids with strange rashes. Persistent coughs.

“We're in long-term exposure,” he says. “I never had a symptom until a week ago. We've been finding out that the people who never left town are showing symptoms.”

His story isn’t that different from Joy Mascher’s—and other local business owners. They couldn’t shut down. Dave owns a high-performance automotive shop. They had no other choice but to work—despite the tragedy and all the unknown variables.

A big guy who I could tell was a fighter because of his cauliflower ear comes up to us and asks Dave how he’s doing. He’s holding a Ziploc filled with what looks like black dirt. He asks Dave about the guy with the gun yesterday, but he’s more concerned about Dave’s symptoms. He tells us about the contents of the bag. He says it’s from 45 feet below the most nutrient rich peat bog in the world—according to him. He says it has healing capabilities. He says it’s worked on him. He says it fixes everything from illnesses to brain fog.

He hands Dave a bottle of the stuff, and then says we should both try it. I would be remiss to turn down what will either be some ancient cure from below the Earth’s surface—or—as Dave puts it—it could just be some mud water.

The bartender hands us two bottles of water. We pour in a spoonful of the dirt and watch it sink to the bottom. The whole bottle turns blackish brown in seconds. It tastes the way the air smells after rain on a spring day. I’m either consuming something restorative, or I’m poisoning myself. But it seems like a risk just spending all this time in East Palestine regardless. So many people in town made it seem like staying in town was a death wish. But they have no other options.

I take another swig of the peat bog water and see someone I recognize standing on the other side of the steakhouse. It’s a man with dark grey hair and a green jacket and a circle of people has formed around him. I squint and realize it’s Steve Bannon recording a show. Supposedly, President Trump called in yesterday and Dave missed the chance to speak with him by 15 minutes.

“If our government can’t take care of East Palestine, how are we supposed to take care of the rest of the country?” I ask.

“Spray this from helicopters,” the man says holding up his bag of dirt.

Dave says he’s gone to his doctor about the symptoms. He claims that his doctor said that since he lives in East Palestine, he can’t help him.

“My own doctor dismissed me,” he says. “He told me I need to find a new doctor. I asked for my medical records from the past two years so I can show my baseline of health. I've never had these issues before.”

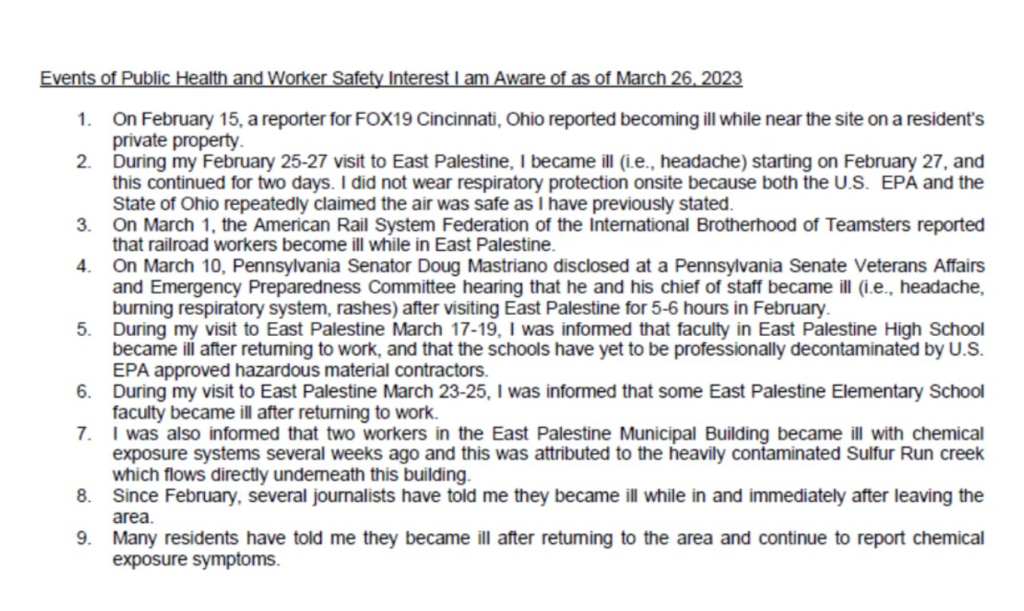

I bring up a story I heard yesterday about a professor named Andrew Whelton who submitted a FOIA request to the CDC about different workers who got sick being here. Whelton claimed to become ill when he visited East Palestine from Feb. 25-27. He lists a number of accounts of officials, residents, and clean-up crews who seem to have been sick from the contamination.

As of April 3, this information was available on the Ohio Emergency Management Agency’s website: "For several weeks, the Ohio Department of Health, in conjunction with federal partners, has been surveying East Palestine residents and first responders to the derailment site about health symptoms experienced related to the derailment."

These surveys, called ACE (after chemical exposure) surveys, closed last Friday (March 31st) at midnight for data analysis.

Of 212 respondents to the first responder survey, the top five symptoms reported were:

A random person claiming to be with some media company calls the Roadhouse and the bartender decides to hand Dave the phone. He says he’s too tired for this shit, but puts the phone to his ear. He tells the guy on the phone that if he wants he can talk to me, as if I’m going to be any more of a help. Whatever the guy is saying, Dave isn’t in the mood, so he hangs up.

“It’s a lot right now… everything I’m going through,” he says.

“I can’t imagine,” I say.

I tell Dave I’m going to head back to the EPA to see if I can finally get some answers.

“Just tell them you were with Petey. They love this dog… They will be jealous and mad that you didn’t bring Petey… They all know me there,” he says and reaches for another White Claw. *

Unfortunately, I don’t get to meet anyone in person at the EPA office. But these are the answers their Public Information Officer emailed me. (I have asked a few follow-up questions regarding what Dave said about the address of the jobsite moving. I have yet to hear back.)

Q: What services are you providing for the community?

A: As the lead responding Agency, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has supervised Norfolk Southern and worked collaboratively with other state and local agency’s environmental testing and cleanup work at and near the site. Additionally, EPA has been leading the effort to conduct environmental testing and remediation for local residential and business community.

In the last few weeks, EPA began convening a weekly Community Forum at the East Palestine Public Library, for community members to have two-way communication directly with EPA. EPA also entered into an agreement with the village of East Palestine to provide the community access to technical assistance through EPA’s Technical Assistance Services for Communities program. They will provide the community direct access to science resources (at no cost) to help interpret technical work, regulations, and environmental policies that surround the train derailment emergency and response efforts.

Q: What are some of the frequently asked questions your office is fielding from residents of East Palestine?

A: Resident questions include the following:

· Exposure to chemicals in the air, soil and water (dioxins in particular)

· Chemicals of concern from the site and their associated health impacts

· Residential soil sampling and water testing

· Physical work updates, road closures, and upcoming public meetings

· Livestock and pet health impacts

· Odors and toxicity

· Environmental testing results

· Impacts to the environment

Q: Would you be able to speak on the nature of the inversion that happened in the atmosphere after the chemical burn?

A: The smoke plume was emitted vertically into the atmosphere on the evening of February 6 and dispersed to the southeast initially and then to the east. Dispersion of smoke emitted into the atmosphere is dependent on wind patterns and vertical air movement. Monitoring collected near the incident did not show exceedances of screening levels with the exception of PM2.5. Smoke is comprised of a mixture of particulate matter and gases and can have a range of health effects. Generally, concentrations of air pollutants and associated health risks decrease with distance.

Q: I’d like to understand the process and decision of removing the contaminated land from East Palestine to places such as East Liverpool.

A: Responsible Parties conducting cleanups at sites send hazardous wastes to facilities permitted to receive them by EPA or a state under an authorized RCRA hazardous waste program. These facilities must also be on EPA’s list of facilities that are qualified to receive the waste materials under the EPA’s Off-Site Rule. 40 C.F.R. § 300.440. Many facilities across the country are permitted to receive and dispose of the waste Norfolk Southern is removing from the Site. Facility assessment, feasibility, and contracting of the receiving facilities are the responsibility of Norfolk Southern.

Q: What are the EPA’s concerns about chemicals such as dioxins?

A: EPA is very concerned about residents feeling safe at home again. The community has expressed concerns on increased dioxin levels that may be associated with the chemicals burned during the fire. In response EPA has required Norfolk Southern to sample directly for dioxins under the Agency’s oversight as well as conduct a background study to compare any dioxin levels around East Palestine to dioxin levels in other areas not impacted by the train derailment. By testing for dioxins and other chemicals, residents will be provided with results that will help them understand what’s in their environment.

Q: Is Norfolk Southern in charge of the testing on the site?

A: No. EPA’s Federal On-Scene Coordinator is in charge of testing on the site under the Unilateral Administrative Order for Removal Actions (February 21, 2023, as amended). Norfolk Southern, and its contractors are physically conducting testing at most of the site under the workplan approval and supervision of EPA. EPA contractors are conducting residential soil testing, and the State of Ohio is conducting sampling and cleanup work in the Sulphur and Leslie Runs.

Q: How was the decision made to burn the chemicals? Why did the EPA believe this was the best option (and can you discuss what other possible options were)?

A: EPA did not order the controlled burn. The incident commander made the decision in consultation with Norfolk Southern, local law enforcement, and response officials from Ohio. We recommend that you reach out to local and state responders for a comment.

Q: Is the EPA testing local livestock for contamination? (Some locals have claimed their bees have died in the wake of the chemical burn. Can the EPA speak to this—whether they believe there could be a connection?)

A: According to the Ohio Department of Agriculture Livestock and Pet FAQs, there is no indication there is an increased risk to livestock following the incident. Although there is no indication that the drinking water is unsafe to consume, residents on well water should call to have their private wells tested as soon as possible (330-849-3919) to ensure residents, livestock, and other animals are not impacted.

Q: Was the EPA involved with the decision to bring back residents after evacuating for the chemical burn?

A: The Ohio Governor Mike DeWine and Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro ordered the evacuation in a one-mile by two-mile area surrounding East Palestine, which includes parts of both Ohio and Pennsylvania. Please reach out to their office for their decision-making process.

Q: Is it possible that the wreck site could become a candidate for a brownfield fund?

A: EPA’s Brownfields program has grant funding for property owners who meet eligibility requirements. Sites with a viable responsible party are not typically eligible for Brownfield funds.

Q: What are the EPA’s long-term goals with East Palestine? For instance, will testing and monitoring continue for years to come?

A: EPA continues to lead cleanup work at the site for the foreseeable future. No decisions have been made on long-term goals on testing or monitoring at this time.

I have reached out to the mayor of East Palestine and the governors of Ohio and Pennsylvania. They have yet to respond.

However, it was during my last day in town when the EPA announced an investigation into the decision to explode the freight trains. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Justice has sued Norfolk Southern to ensure they pay for the entire cleanup. *

Before I leave East Palestine, I hear news of multiple barges crashing in the Ohio River six hours south of here near Louisville. They were reportedly carrying methanol which is incredibly toxic when it meets water. As of now, officials say there has been no leaked methanol detected during the cleanup process.

There is a distortion in these tragedies where the information people are receiving cancels itself out. One official will say something is safe, another expert will say it’s harmful. This creates a limbo of unease. People of East Palestine have witnessed anomalies in the aftermath of the explosion. Perhaps they are just coincidences. Multitudes of dead fish have been reported. No one has yet to explain why thousands of bees died in a local apiary. Parents are unsure what the rashes on their children mean. The most dreadful thought is that these people might not have answers for years.

People keep referring to East Palestine as a Chernobyl-level event—both in terms of toxicity and bureaucratic incompetence. Residents fear they’re becoming the next Flint, Michigan, but I fear it could be much worse than that. I pray it’s not, but the levels of dioxins will determine the decay (or hopefully rebirth) of East Palestine.

Dioxins have wiped entire towns off the map before. Times Beach, Missouri is one example. The town used dioxins to spray on top of dust and eventually the entire town had to be evacuated permanently and the federal government absorbed the land. (After you read up on Times Beach, and if you can stomach more incompetence, you can look into the Seveso Disaster, or what is sometimes referred to as Italy’s Hiroshima.)

Earth feels like it’s become a prison planet run by governments and corporations that are immune from accountability—and they’ve poisoned every inch of the place.

A recurring theme in East Palestine is that most people’s faith in the government is at an all-time low. They have each other to lean on—and they are grateful for their neighbors and for outsiders who’ve come to pitch in—but the disaster can have devastating impacts that will extend far into their future. They fear for the health of their children. Will they get cancer from exposure to dioxins? Will there be any adverse reproductive symptoms? Will they ever feel safe eating from their own gardens? Can they eat the deer they hunt? Will the value of their homes continue to plummet? Will anyone be held accountable?

How can a country sustain itself under the weight of every ill-managed disaster? The people of East Palestine watch the news as each new tragedy occurs, they see the media and politicians descend for a photo op, whether they like them or not, and then the help disappears, and they’re left loading up each other’s cars with water bottles from the pallets stacked up behind the First Church of Christ.

I’ve got the radio on as I leave town and I hear the mayor of Philadelphia, Jim Kenney, talking about the recent chemical spill in the Delaware River. Chemicals that are used to make headlight covers leaked into the river.

Kenney was asked about the surge of Philadelphia residents buying bottles of water, fearing that their tap water is now dangerous.

“There’s people buying ten cases of water,” he said. “It’s pretty selfish.”

And then, Mike Carroll, the deputy managing director for Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability in Philadelphia, did the classic photo-op of himself drinking a glass of tap water.

“It’s safe. It’s contaminant-free. And we can all enjoy it to drink. To cook with. To wash with. Whatever you want. So I will drink to that,” he said and took a swig.

These displays of pseudo-confidence-building do nothing. They are empty gestures. Band-Aids over bullet holes.

Our country is engulfed in flames and riddled with poison as our politicians take sips of water to make us feel better. No one is buying the routine anymore.